Maria de Medeiros

Patron of the Fourth Edition "Pavillon Les Cinémas du Monde"

Since Maria de Medeiros was 15 years old, the actress, director and singer has had a brilliant international career in theatre and cinema. She is true to her Portuguese roots, but has chosen France as her country of adoption and speaks several languages fluently. In her own words, she is a “film globetrotter”, and her personal and artistic commitments build bridges between northern and emerging countries, from Portugal to the United States, Brazil and Mozambique. In 2007, she was on the Cannes Film Festival jury. This year, she is back to support the Cinémas du Monde Pavilion’s artistic delegation.

“I am undoubtedly the product of France’s global cultural influence. Well before I moved to Paris and became a French citizen, I grew up with the language spoken by Ronsard, Baudelaire and Rimbaud—as I grew up with the language of Pessoa. I was an admirer of impressionism, existentialism, Léo Ferré, Georges Brassens, Jacques Prévert, Jacques Tati and François Truffaut. My schooling took place in international French schools. These institutions welcomed children from around the world, who all reflected the spirit of French culture. This spirit, which I still love, is characterised by curiosity, attention to what is different and an unfailing support for culture—all the world’s cultures. I am therefore extremely proud to be supporting the artists presenting their projects in 2012 at the Cinémas du Monde Pavilion. Taking in Paraguay, Chile, Brazil, Burma, Rwanda, Vietnam, Tunisia, Iran, Palestine and Madagascar, this tour of world cinema already promises to be full of discoveries. I would like to thank the Festival de Cannes for welcoming us, and showcasing the many different voices of cinema.”

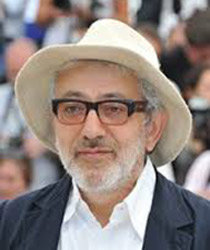

Elia Suleiman

Patron of the fourth Edition "Pavillon Les Cinémas du Monde"

“Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suleiman is best known for his 2002 film Divine Intervention (awarded the Cannes Jury Prize), which pushed him into the international spotlight. Since his first feature-length film Chronicle of a Disappearance (awarded best debut film prize at the Venice Film Festival), he has developed a unique body of work, which is both poetic and political. Often compared to Tati and Buster Keaton, he acts in his own films, and deals with serious themes – like the consequences of the Israel-Palestine conflict – in unconventional ways. This gives his films a universal dimension. In 2006, he sat on the Cannes Film Festival jury, and in 2009, entered the official competition with The Time That Remains. This year, he will support the Cinémas du Monde Pavilion’s artists.

“When I came to Paris the first time in search of a producer for my first feature film Chronicle of a disappearance, I was going from one address of a producer’s office to another by walking. I did not venture into the metro too often because it took me too long to get there; I was either constantly getting lost, or heading the wrong direction, and mostly, because I spent too long trying to find the ‘sortie’ which back then I did not know what it meant. The few producers who accepted to see me in order to explain to me why they have rejected my script were undoubtedly from the leftist political spectrum. Their solidarity with the long list of just causes in the world was evident from the film posters hanging on their office walls. I figured that it was due to a feeling of solidarity that they wanted to spare the time to give me a piece of advice. But I found out, in fact, that they invited me because they were curious, or rather baffled, or as in one case, annoyed.

They wanted to know what kind of Palestinian was I, if I was at all. “Your script is not Palestinian enough”, “I find absolutely nothing Palestinian in your script; this story can happen anywhere in the world” or “your characters are either passive or defeated; how can a people under so much oppression offer no resistance at all”, so they said in so many words. But if it can happen anywhere in the world, why can’t it happen in Palestine, I asked myself. One producer gave me the contact of a leftist Israeli filmmaker maybe he could understand me better! We met in a café under his flat and he went on a rage accusing me of being an American puppet (I was living in New York at the time). Years later, I produced my film myself. One favorable review, I remember, declared innocently saying, “yes it’s Palestinian but it’s not what you think !”

Many years and a few films later, I’m less and less represented as ‘the Palestinian film director’, and the more and more, the emphasis is shifting away from ‘Palestinian’, without having to be more or less Palestinian. I have faith, that one day, cinema will no longer be attached to national identities. Cinema does not recognize borders and cannot be halted at checkpoints; the question of identity will one day be deemed irrelevant. The vanishing era of post-coloniality may continue to insist on keeping it’s culture running, but it is undeniably running on empty. It is uncertain to me if post-colonialism had lost to resistance or to the vanquishing armies of the new world order or to both. Nonetheless, an industrial revolution, of some two hundred years, which largely contributed to the devaluation of time and the shrinking of space, had finally shot itself in the foot. The camera for one, which it invented, and was used as a tool for war, had turned against its creator and despite itself, gave rise to the cinema.

The virtual boundaries between ‘East’ and ‘West’, ‘North’ and ‘South’ have been collapsing for a while and they continue to crumble. Cinema can glance inward to shed light on itself without needing a reflex mirror of what the ‘Other’ wishes it to be. We have recently witnessed the events of the Arab and non-Arab springs that shook the earth under the clusters of powers, shattering the mirrors of their globalized decadence and their reflected representation. The fear and anxiety, which were installed, have boomeranged against its creators. If the aim of the virtual financial market was and still is the occupation of the world, cinema persists to deter the implausible occupation of the soul. Glancing inward, I can imagine, desire, love and daydream.

What is imagined, yet invisible to others, can potentially become visible, can be shared, it’s communicability already felt at the moment it is daydreamed. Interiorly, sporadic flashes of light are released, float in a cosmos without gravity. The seeming disorder of the shining particles, have a magnetic attraction, one to another, and one to the whole. They promise harmony so I wait. But chaos persists and that makes me anxious. But instead of wait, I must activate; I must participate. I take a leap. True that nothing is reassuring. But I will always have something to cling to; there is always hope. This is how Cinematography can begin.”

Maria de Medeiros and Elia Suleiman follow in the footsteps of Elsa Zylberstein and Pablo Trapero (2011), Sandrine Bonnaire and Rithy Panh (2010) and Juliette Binoche and Abderrahmane Sissako (2009).